Fresnel equations

The Fresnel equations (or Fresnel conditions), deduced by Augustin-Jean Fresnel (pronounced /freɪˈnɛl/), describe the behaviour of light when moving between media of differing refractive indices. The reflection of light that the equations predict is known as Fresnel reflection.

Contents |

Explanation

When light moves from a medium of a given refractive index n1 into a second medium with refractive index n2, both reflection and refraction of the light may occur.

In the diagram on the right, an incident light ray PO strikes at point O the interface between two media of refractive indices n1 and n2. Part of the ray is reflected as ray OQ and part refracted as ray OS. The angles that the incident, reflected and refracted rays make to the normal of the interface are given as θi, θr and θt, respectively. The relationship between these angles is given by the law of reflection: θi = θr ; and Snell's law: sin(θi) / sin(θt) = n2 / n1 .

The fraction of the incident power that is reflected from the interface is given by the reflectance R and the fraction that is refracted is given by the transmittance T.[1] The media are assumed to be non-magnetic.

The calculations of R and T depend on polarisation of the incident ray. If the light is polarised with the electric field of the light perpendicular to the plane of the diagram above (s-polarised), the reflection coefficient is given by:

where θt can be derived from θi by Snell's law and is simplified using trigonometric identities.

If the incident light is polarised in the plane of the diagram (p-polarised), the R is given by:

The transmission coefficient in each case is given by Ts = 1 − Rs and Tp = 1 − Rp.[2]

If the incident light is unpolarised (containing an equal mix of s- and p-polarisations), the reflection coefficient is R = (Rs + Rp)/2.

Equations for coefficients corresponding to ratios of the electric field amplitudes of the waves can also be derived, and these are also called "Fresnel equations". These take several different forms, depending on the choice of formalism and sign convention used. The amplitude coefficients are usually represented by lower case r and t. In some formalisms they satisfy:

At one particular angle for a given n1 and n2, the value of Rp goes to zero and a p-polarised incident ray is purely refracted. This angle is known as Brewster's angle, and is around 56° for a glass medium in air or vacuum. Note that this statement is only true when the refractive indices of both materials are real numbers, as is the case for materials like air and glass. For materials that absorb light, like metals and semiconductors, n is complex, and Rp does not generally go to zero.

When moving from a denser medium into a less dense one (i.e., n1 > n2), above an incidence angle known as the critical angle, all light is reflected and Rs = Rp = 1. This phenomenon is known as total internal reflection. The critical angle is approximately 41° for glass in air.

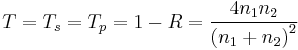

When the light is at near-normal incidence to the interface (θi ≈ θt ≈ 0), the reflection and transmission coefficient are given by:

For common glass, the reflection coefficient is about 4%. Note that reflection by a window is from the front side as well as the back side, and that some of the light bounces back and forth a number of times between the two sides. The combined reflection coefficient for this case is 2R/(1 + R), when interference can be neglected (see below).

The discussion given here assumes that the permeability μ is equal to the vacuum permeability μ0 in both media. This is approximately true for most dielectric materials, but not for some other types of material. The completely general Fresnel equations are more complicated.

Effect from multiple surfaces

When light makes multiple reflections between two or more parallel surfaces, the multiple beams of light generally interfere with one another, resulting in net transmission and reflection amplitudes that depend on the light's wavelength. The interference, however, is seen only when the surfaces are at distances comparable to or smaller than the light's coherence length, which for ordinary white light is few micrometers; it can be much larger for light from a laser. An example of this effect is the iridescent colours seen in a soap bubble or in thin oil films on water. Applications include Fabry–Pérot interferometers, antireflection coatings, and optical filters. A quantitative analysis of these effects is based on the Fresnel equations, but with additional calculations to account for interference.

The transfer-matrix method, or the recursive Rouard method[4] can be used to solve multiple-surface problems.

See also

- Index-matching material

- Fresnel rhomb, Fresnel's apparatus to produce circularly polarized light [1]

- Specular reflection

- Schlick's approximation

References

- ↑ Hecht (1987), p. 100.

- ↑ Hecht (1987), p. 102.

- ↑ Hecht (2002), p. 120.

- ↑ see, e.g. O.S. Heavens, Optical Properties of Thin Films, Academic Press, 1955, chapt. 4.

- Hecht, Eugene (1987). Optics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-11609-X.

- Hecht, Eugene (2002). Optics (4th ed.). Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-321-18878-0.

External links

- Fresnel Equations – Wolfram

- FreeSnell – Free software computes the optical properties of multilayer materials

- Thinfilm – Web interface for calculating optical properties of thin films and multilayer materials. (Reflection & transmission coefficients, ellipsometric parameters Psi & Delta)

- Simple web interface for calculating single-interface reflection and refraction angles and strengths.

- ReflectionCoefficient.INFO – Optical reflection coefficient calculator

- Reflection and transmittance for two dielectrics – Mathematica interactive webpage that shows the relations between index of refraction and reflection.

![R_s =

\left(\frac{n_1\cos\theta_i-n_2\cos\theta_t}{n_1\cos\theta_i+n_2\cos\theta_t}\right)^2

=\left[\frac{n_1\cos\theta_i-n_2\sqrt{1-\left(\frac{n_1}{n_2} \sin\theta_i\right)^2}}{n_1\cos\theta_i+n_2\sqrt{1-\left(\frac{n_1}{n_2} \sin\theta_i\right)^2}}\right]^2](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/47a46e2ab7bcfaf62412e71f8aa2a6ae.png)

![R_p =

\left(\frac{n_1\cos\theta_t-n_2\cos\theta_i}{n_1\cos\theta_t+n_2\cos\theta_i}\right)^2

=\left[\frac{n_1\sqrt{1-\left(\frac{n_1}{n_2} \sin\theta_i\right)^2}-n_2\cos\theta_i}{n_1\sqrt{1-\left(\frac{n_1}{n_2} \sin\theta_i\right)^2}+n_2\cos\theta_i}\right]^2](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/23d528111d8a241129e6a804c052294c.png)